Conserving Information by Scaling the Stratum

We are on the cusp of enormous advances in the way we feed populations and look after the Earth.

Humans are rapidly evolving in their use of ‘systems thinking.’ Around the world, people have come to understand there are delicate interdependencies between natural resources, human activities and environmental factors.

This holistic way of thinking is already driving policy changes – such as the banning of some single use plastics in response to their detrimental impact on the ocean and seafood. However, to address the major threats facing our food system and environment, it’s vital for policymakers and primary producers to take systems thinking to the next level.

That’s where data comes into the picture. For more informed decisions, there is a pressing need to integrate related data from sources throughout the primary industries. This includes obvious datasets, as well as relatively novel sources of information that can tell us what is happening in the hidden side of nature – such as invisible chemical emissions that provide early warnings about dangers to crop health.

Optimised data management can lead to enhanced food security, more efficient agricultural practices, more nutritious and safe food, reduced waste and improved logistics.

In this article, I will explain how technology-enabled real-time feedback loops can assist us in governing natural capital. In particular, I examine the use of advanced sensing technologies, and how these can assist data-driven decision-making in agriculture.

Natural capital

Natural capital encompasses the world's stocks of natural resources – such as geology, soils, air, water, and all living organisms – that provide essential goods and services to humanity.

A systems-thinking perspective reveals how the health of one component influences the resilience of the entire system. For instance, healthy soil supports plant growth, which in turn provides food, raw materials, and habitats, while its degradation triggers cascading effects that disrupt ecological stability and economic security.

Changing climatic patterns and biodiversity loss further threaten the productive capacity of natural resources, impacting biosecurity and established supply chains.

Concepts like ‘Planetary Health’ and ‘One Health’ stress the need for integrated approaches that balance the wellbeing of people, animals, and ecosystems (Morrison et al. 2022). By embracing systems thinking, we can foster collaborative solutions that sustain and regenerate natural capital for future generations.

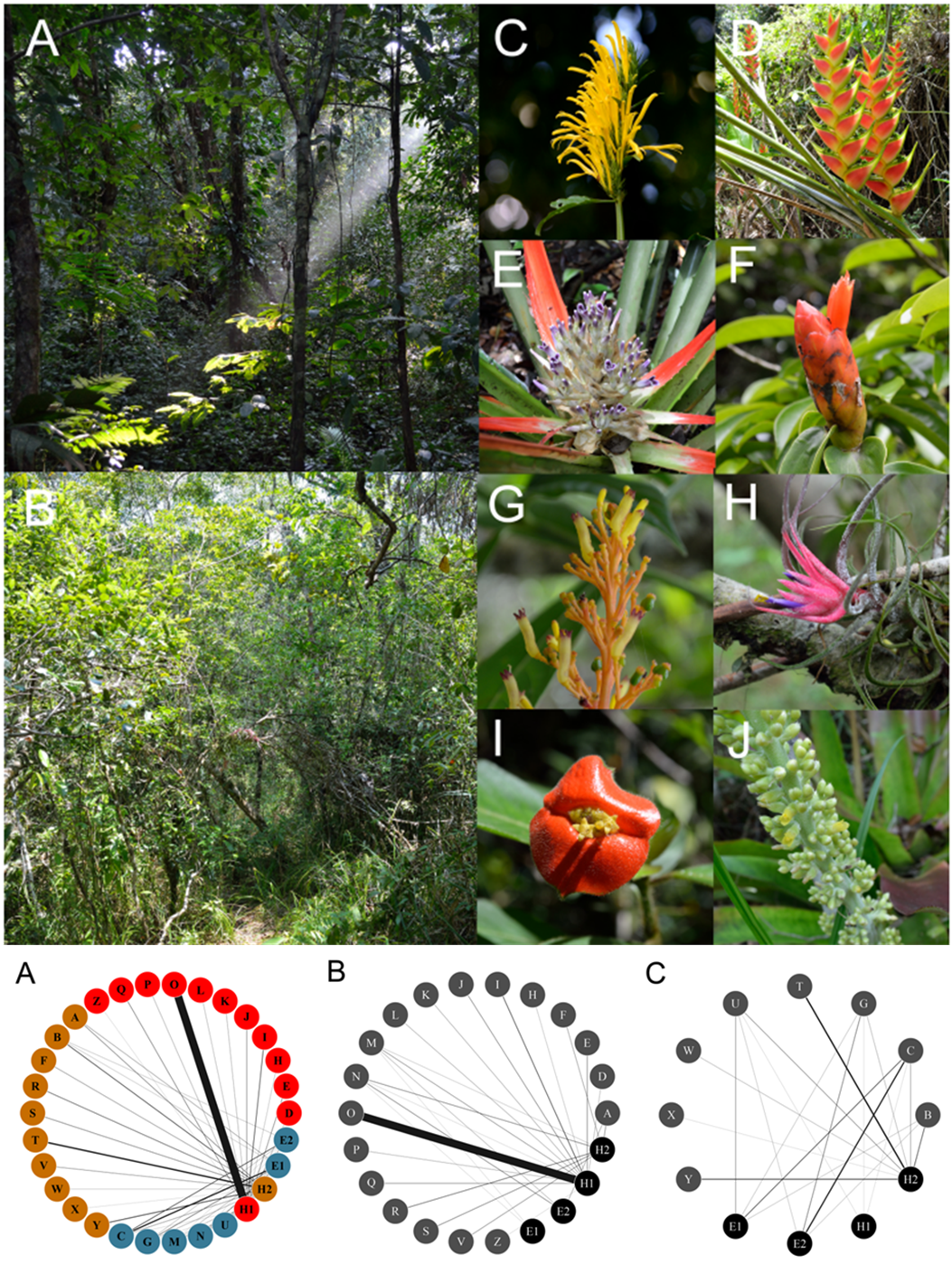

Hidden links

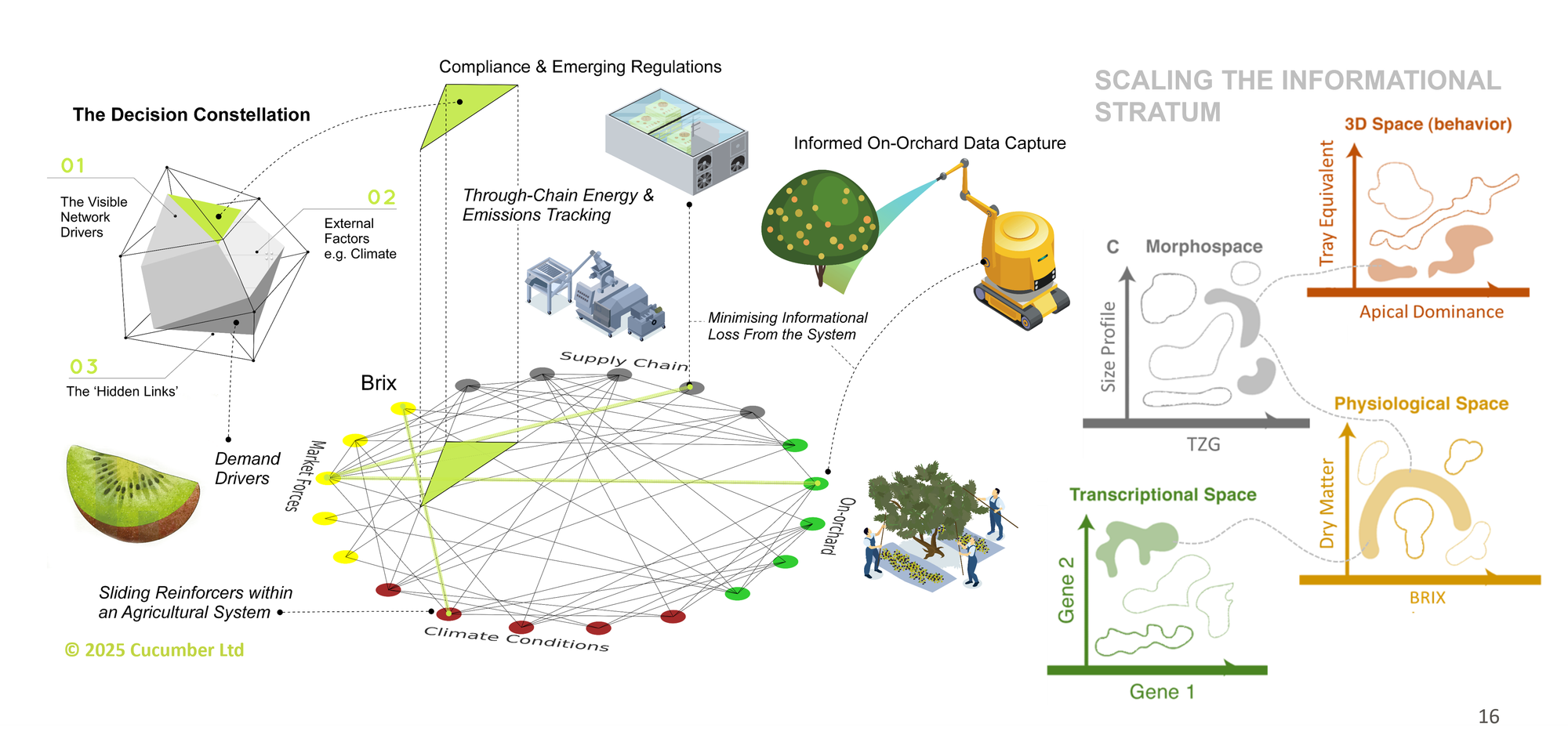

At first sight, these seemingly discrete sub-systems of this illustrated One Health ecosystem do not seem to be clearly correlated. However, in 1931 the Russian evolutionist Paul Terentjev, described how in organisms within nature there are correlations among measurable characteristics of seemingly discrete elements, making these elements a cluster, or Pleiades (Berg 1960). This became known as a 'correlation pleiades', which can be discovered throughout nature's complex systems, but often veiled as hidden patterns or forbidden links (Izquierdo-Palma et al. 2021).

Not all relationships are easily recognisable. Discovering these ‘hidden links’ is very important since they might also serve as network drivers and resemble 'organic' network control systems, which if better understood, could support much improved decision-making capabilities(Gautam et al. 2021).

However, when these network drivers are not properly understood, we can often experience sudden and unforeseen consequences. Complex systems have a habit of backfiring in unforeseen ways, which is equally true in wildlife conservation. One such non-linear feedback mechanism is called sliding reinforcers (Cumming 2018).

"In conservation contexts, sliding reinforcers can include such phenomena as the construction of infrastructure (roads may allow an area to benefit from ecotourism, but also facilitate the entrance of undesirable influences, such as poaching); … pesticide and fertiliser use (small amounts can improve crop yields, but overuse harms the environment) …. Feedbacks may influence the values of two variables of interest in the same direction simultaneously, meaning that correlations and other simple statistics are not suited to detecting them" (Cumming 2018).

In this era of extraordinary environmental challenges, understanding the complex interdependencies within our natural ecosystems is more crucial than ever (Theise 2023). Systems thinking offers a powerful framework for co-creating resilient natural capital that is beneficial for indigenous custodians and stewards of the land (such as farmers and growers) as well as consumers .

Adaptive management and real-time feedback loops

An example – Our greenhouse project

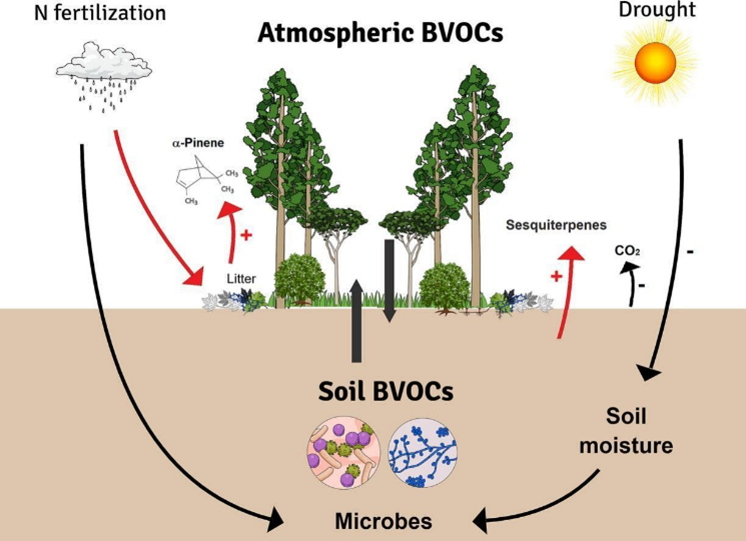

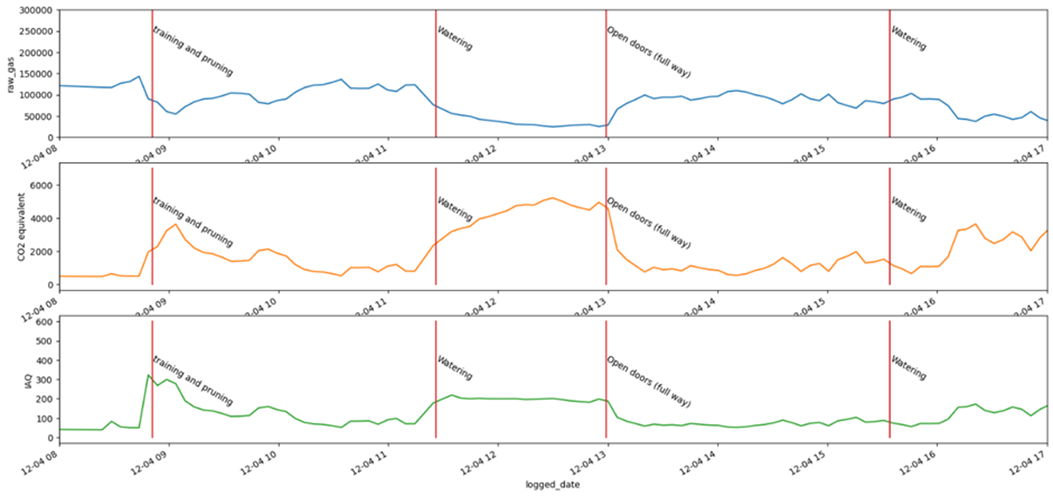

At Cucumber, we are embracing this new paradigm. Our technology provides information about the “hidden links” in nature. By measuring and interpreting the molecular realm, such as Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds, we unlock an entirely new realm of data.

The invisible, organic compounds released by crops and forests provide valuable information. This includes early warnings of any stress to plants that might lead to lowered defence mechanisms or reduced quality.

Our technology embodies systems thinking by enabling the integration of various data sources to manage natural capital effectively.

Our sensor technology can provide real-time feedback to primary producers, allowing for:

- Rapid detection of any changes in plants / produce

- Immediate analysis of data

- Quick responses to emerging issues.

We employ a range of innovative sensing technologies, ranging from Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) through to novel photonic systems, which ensures granular data provenance.

These advanced tools enable us to conserve the informational flow from the biome through to decision-making, enhancing our ability to respond to environmental changes promptly. The technology can accurately define the root-causes of issues presenting within a system. This enhances our ability to design-in resilience and respond rapidly to evolving circumstances, such as pathogens and pests.

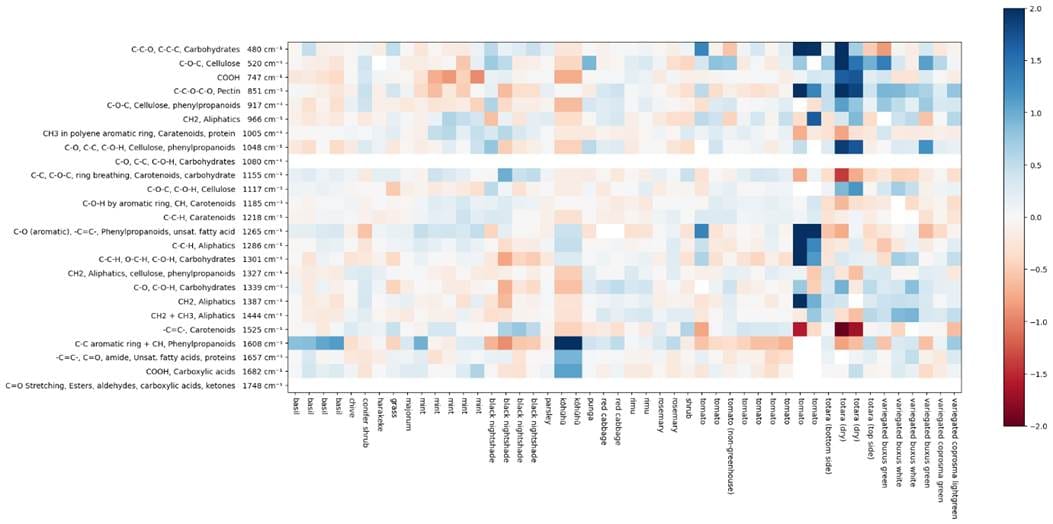

Tomato plants emit various VOCs, including terpenes like isoprene, monoterpenes, and sesquiterpenes (Lee Díaz et al. 2022; J. Li, Di, and Bai 2019; Nawrocka et al. 2023; Takayama et al. 2012; Dehimeche et al. 2021). These compounds are pivotal for plant communication and stress responses, making them valuable bio-proxies for event-monitoring that occur at the resource, with use cases such as optimal growth, emissions tracking and pathogen detection.

BioCanvas platform

Interpreting on-field Events via bio-physical signalling i.e. BVOCs

Technologies that foster radical transparency within supply chains

By utilising novel photonic sensing approaches to fingerprint produce, we open up possibilities to accurately differentiate between biotic and abiotic stresses within plants (B. Li et al. 2020; Park et al. 2023; Bolaji Umar et al. 2022). This precision enables us to minimize unnecessary use of synthetic pesticides or biopesticides, leading to improved localized resource management and reduced agricultural losses.

Fostering adaptable and agile supply chains

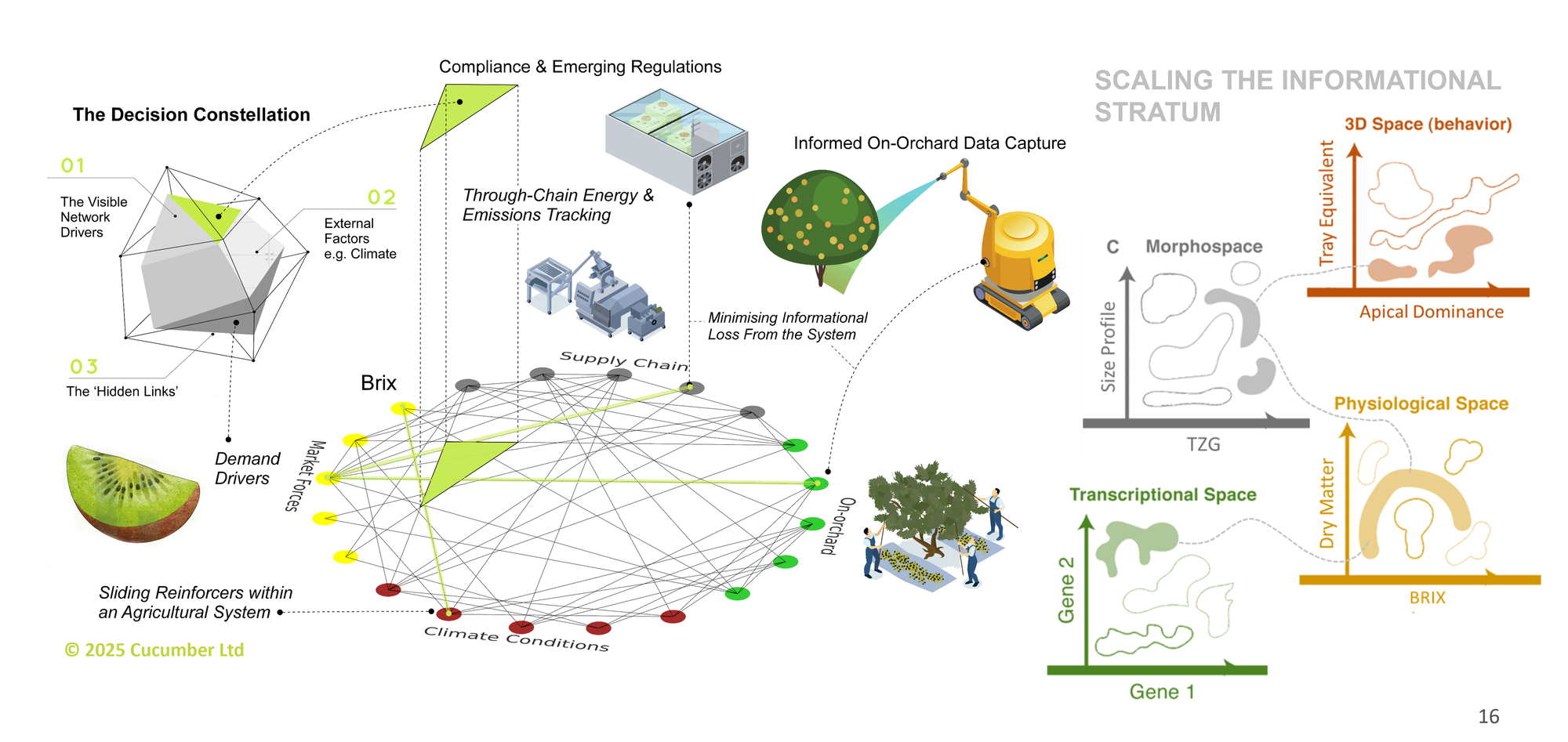

A kiwifruit industry example

In today's data-driven agricultural landscape, breeders and growers face significant challenges in managing and using vast amounts of data.

Breeders of kiwifruit are tasked with sifting through extensive, often inconsistent datasets to select individuals for advancement, a process complicated by missing information, fuzzy correlations between stages, and the need to balance trade-offs between traits.

Inefficiencies arise from dispersed data and incomplete records, making it difficult to optimise breeding selections and manage resources effectively. Additionally, integrating genetic and phenotypic data to extract actionable insights remains a critical hurdle.

Addressing these pain points requires innovative solutions such as advanced decision-support tools, machine learning models, and improved data capture practices to streamline analysis, enhance decision-making, and drive efficiencies in breeding programs.

Applying a systems-thinking approach to the kiwifruit example:

- Conventional data-capture methods often overlook critical data points, leading to an incomplete understanding which represents itself as ‘loss of information’ within supply chain ecosystems. This inherently limits the information available for decision-making.

- There is a pressing need for cost-effective, portable detection systems that yield data which can link with other contextual data sources, including domain-specific data ontologies, to create a comprehensive view of ecosystem health and optimal productive state. This can help unpack ‘the hidden links’ and provide for more informed and effective decision making.

- In terms of bi-lateral compliance and export readiness, there is a critical need for solutions that can automate and augment compliance reporting, via means such as digital certificates (e.g. certificates of low prevalence), providing stakeholders with assurance that practices are compliant with local and global standards.

Systems thinking underpins adaptive management by promoting iterative cycles of action, monitoring, and insight (Allen and Kilvington, n.d.; Boardman and Sauser 2008).

Scaling the stratum - Biogenic data as a ‘product’ with provenance

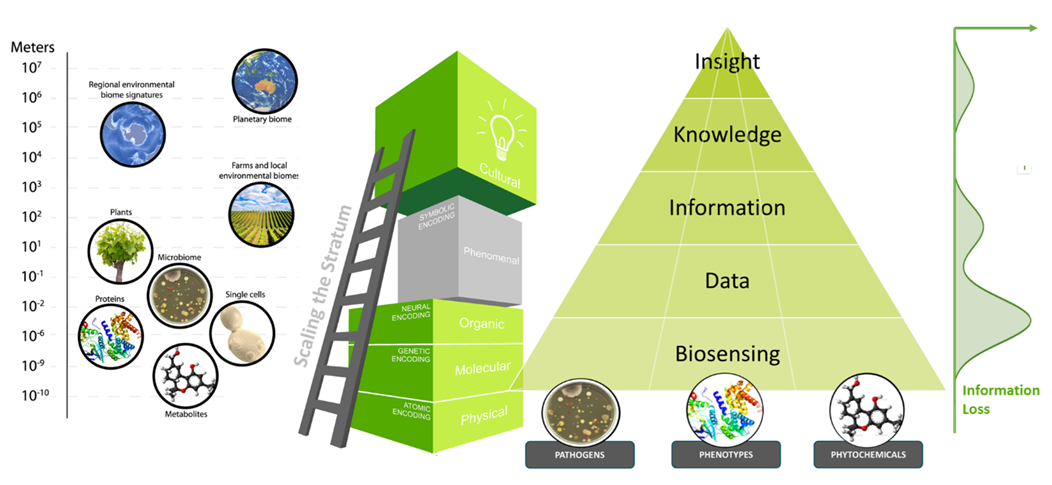

In today's data-driven world, biogenic data – information derived from biological processes – is a precious asset. However, much of this data is currently lost or underutilised.

If we want to make better decisions in agriculture and environmental management, we need to track and preserve this kind of information much more carefully. For an example of how this is done well, we can look to nature itself.

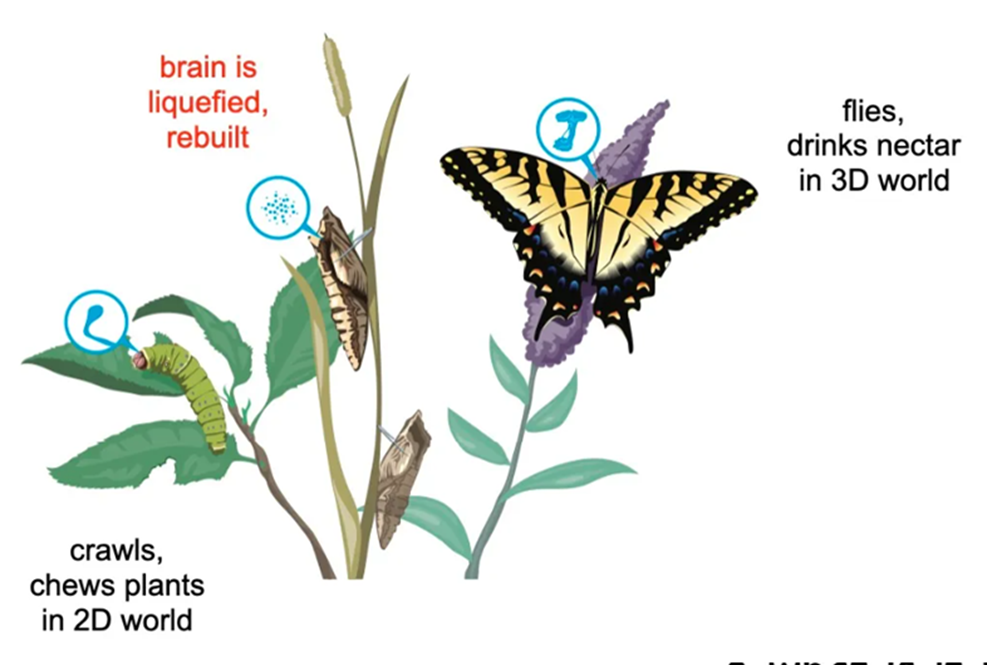

Nature is an efficient custodian of information, conserving data through mechanisms like the mass-energy-information equivalence principle, as manifested through scale-invariant phenomena ranging from Hawking radiation through to how memories tend to be generalised and conserved through to new architectures (Vopson 2019; Levin 2022; Blackiston, Shomrat, and Levin 2015).

“But any life that is vigorous and open to challenge and compassion and the real activity of thought knows that, as we journey, we create many tabernacles of absence within us. Yet, there is a place where our vanished days secretly gather. Memory, as a kingdom, is full of the ruins of presence. It is fascinating that, in your memory, nothing is lost or ever finally forgotten.” (Walking in Wonder, John O’Donohue)

It seems John O'Donohue was right. Where those memories end up is anybody's guess, but evolutionary biologist Michael Levin and physicists such as Sir Roger Penrose may uncover some hints as part of their groundbreaking research.

This reality suggests that the flow of information is just as fundamental as the flow of energy and matter in maintaining the integrity of natural systems.

“This might explain how spacetime acquires its intrinsic robustness, despite being woven out of such fragile quantum stuff. Some theorists have gone as far as suggesting that spacetime is a quantum code. They regard the lower-dimensional hologram as some sort of source code, operating on a huge network of interconnected quantum particles, processing information and, in this way, generating gravity and all other familiar physical phenomena. In their view the universe is a kind of quantum information processor, a vision that appears only a hair’s breadth away from the idea that we live in a simulation.

Holography paints a universe that is being continually created. It is as if there is a code, operating on countless entangled qubits, that brings about physical reality, and this is what we perceive as the flow of time. In this sense holography places the true origin of the universe in the distant future, because only the far future would reveal the hologram in its full glory.” -Hertog, T., On the origin of time: Stephen Hawking’s final theory, Bantam Books, 2023

Physics has also evolved to reflect this understanding on the nature of information. As Mark Buchanan noted in his book Nexus (Buchanan 2002),

"Physicists, in particular, have entered into a new stage of their science and have come to realise that physics is not only about physics anymore, about liquids, gases, electromagnetic fields, and physical stuff in all its forms. At a deeper level, physics is really about organisation – it is an exploration of the laws of pure form."

The implication is that the network, or the informational architecture of relationships and interactions, is as crucial as the physical entities involved. This understanding naturally extends to biological systems, where the pathways and networks governing biochemical interactions are pivotal.

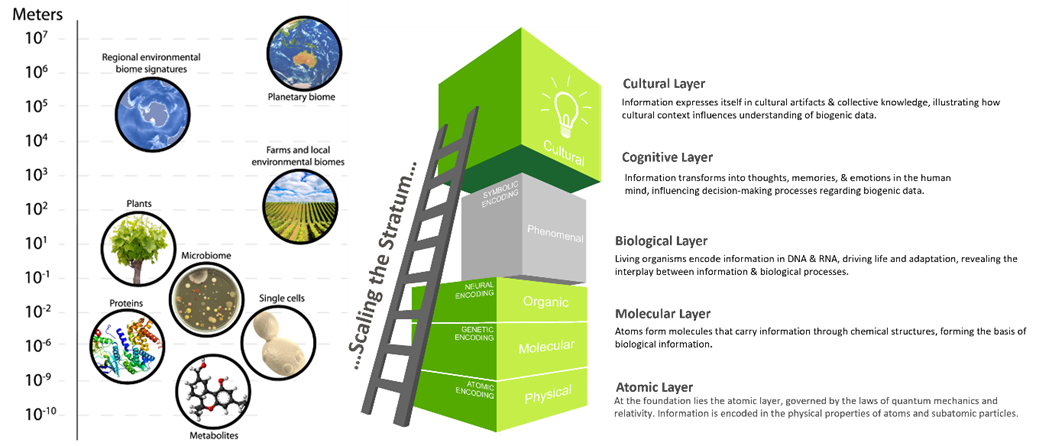

The conservation of information and its flow through various strata – from the molecular level to the biome – reflects an overarching organisational principle. In this sense, biological data becomes more meaningful not just as isolated entities but as part of a broader, interconnected system. This perspective aligns with systems biology, which emphasises that the behaviour of biological systems can't be understood merely by studying individual components. Instead, the interactions and regulatory networks that connect these components are paramount (Kim et al. 2021).

Emulating nature, which excels at preserving and conserving information, can help us minimise data loss and enhance the utility of biogenic data for governance and decision-making. In informational terms, we must treat biogenic data as a “product” to be conserved, ensuring its provenance and integrity throughout the bio-informational stratum.

The journey from molecular data to biome-level insights involves scaling this informational stratum. By integrating molecular data with environmental context, we can discern patterns and trends in ecosystem responses to various stressors. This holistic approach bridges the gap between molecular-level changes and their ecological impacts, facilitating accurate and reliable data-driven narratives.

Scaling the stratum allows us to build data-driven stories that encompass the complexity of natural ecosystems. These stories are constructed by interpreting molecular data within the broader context of environmental conditions, species interactions, and human influences.

Data-driven narratives empower stakeholders with actionable insights that support sustainable ecosystem management. They bridge the gap between scientific research and practical decision-making, fostering a collaborative approach to addressing biomonitoring challenges (Makiola et al. 2020).

References

Allen, Will, and Margaret Kilvington. n.d. An Introduction to Systems Thinking and Systemic Design – Concepts and Tools.

Berg, R. L. 1960. “The Ecological Significance of Correlation Pleiades.” Evolution 14 (2): 171–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1960.tb03076.x.

Blackiston, Douglas J, Tal Shomrat, and Michael Levin. 2015. “The Stability of Memories during Brain Remodeling: A Perspective.” Communicative & Integrative Biology 8 (5): e1073424. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420889.2015.1073424.

Boardman, John, and Brian Sauser. 2008. Systems Thinking: Coping with 21st Century Problems. Industrial Innovation Series. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Bolaji Umar, Olayinka, Lawal Amudalat Ranti, Abdulbaki Shehu Abdulbaki, Abdulra’uf Lukman Bola, Abdulkareem Khadijat Abdulhamid, Murtadha Ramat Biola, and Kayode Oluwagbenga Victor. 2022. “Stresses in Plants: Biotic and Abiotic.” In Current Trends in Wheat Research, edited by Mahmood-ur-Rahman Ansari. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.100501.

Buchanan, Mark. 2002. Nexus: Small Worlds and the Groundbreaking Science of Networks. New York: W.W. Norton. http://www.gbv.de/dms/bowker/toc/9780393041538.pdf.

Cumming, Graeme S. 2018. “A Review of Social Dilemmas and Social‐Ecological Traps in Conservation and Natural Resource Management.” Conservation Letters 11 (1): e12376. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12376.

Dehimeche, Nafissa, Bruno Buatois, Nadia Bertin, and Michael Staudt. 2021. “Insights into the Intraspecific Variability of the above and Belowground Emissions of Volatile Organic Compounds in Tomato.” Molecules 26 (1): 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26010237.

Gautam, Mayank Kumar, Avadh Pati, Sunil Kumar Mishra, Bhargav Appasani, Ersan Kabalci, Nicu Bizon, and Phatiphat Thounthong. 2021. “A Comprehensive Review of the Evolution of Networked Control System Technology and Its Future Potentials.” Sustainability 13 (5): 2962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052962.

Izquierdo-Palma, Jaume, Maria del Coro Arizmendi, Carlos Lara, and Juan Francisco Ornelas. 2021. “Forbidden Links, Trait Matching and Modularity in Plant-Hummingbird Networks: Are Specialized Modules Characterized by Higher Phenotypic Floral Integration?” PeerJ 9 (March):e10974. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10974.

Kim, Youngchan, Federico Bertagna, Edeline M. D’Souza, Derren J. Heyes, Linus O. Johannissen, Eveliny T. Nery, Antonio Pantelias, et al. 2021. “Quantum Biology: An Update and Perspective.” Quantum Reports 3 (1): 80–126. https://doi.org/10.3390/quantum3010006.

Lee Díaz, Ana Shein, Muhammad Syamsu Rizaludin, Hans Zweers, Jos M. Raaijmakers, and Paolina Garbeva. 2022. “Exploring the Volatiles Released from Roots of Wild and Domesticated Tomato Plants under Insect Attack.” Molecules 27 (5): 1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27051612.

Levin, Michael. 2022. “Technological Approach to Mind Everywhere: An Experimentally-Grounded Framework for Understanding Diverse Bodies and Minds.” Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 16 (March):768201. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2022.768201.

Lévy, Pierre. 2011. The Semantic Sphere 1: Computation, Cognition and Information Economy. Oxford$nWiley. London: Iste.

Li, Bin, Rong Wang, Jianjun Ma, and Weihao Xu. 2020. “Research on Crop Water Status Monitoring and Diagnosis by Terahertz Imaging.” Frontiers in Physics 8 (September):571628. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2020.571628.

Li, Jian, Taiju Di, and Jinhe Bai. 2019. “Distribution of Volatile Compounds in Different Fruit Structures in Four Tomato Cultivars.” Molecules 24 (14): 2594. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24142594.

Makiola, Andreas, Zacchaeus G. Compson, Donald J. Baird, Matthew A. Barnes, Sam P. Boerlijst, Agnès Bouchez, Georgina Brennan, et al. 2020. “Key Questions for Next-Generation Biomonitoring.” Frontiers in Environmental Science 7 (January):197. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2019.00197.

Morrison, Margaret, Rafael Trevisan, Prabha Ranasinghe, Greg B. Merrill, Jasmine Santos, Alexander Hong, William C. Edward, Nishad Jayasundara, and Jason A. Somarelli. 2022. “A Growing Crisis for One Health: Impacts of Plastic Pollution across Layers of Biological Function.” Frontiers in Marine Science 9 (November):980705. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.980705.

Nawrocka, Justyna, Kamil Szymczak, Monika Skwarek-Fadecka, and Urszula Małolepsza. 2023. “Toward the Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds from Tomato Plants (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Treated with Trichoderma Virens or/and Botrytis Cinerea.” Cells 12 (9): 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12091271.

Park, Miri, Annette Somborn, Dennis Schlehuber, Volkmar Keuter, and Görge Deerberg. 2023. “Raman Spectroscopy in Crop Quality Assessment: Focusing on Sensing Secondary Metabolites: A Review.” Horticulture Research 10 (5): uhad074. https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhad074.

Takayama, Kotaro, Roel M.C. Jansen, Eldert J. Van Henten, Francel W.A. Verstappen, Harro J. Bouwmeester, and Hiroshige Nishina. 2012. “Emission Index for Evaluation of Volatile Organic Compounds Emitted from Tomato Plants in Greenhouses.” Biosystems Engineering 113 (2): 220–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2012.08.004.

Theise, Neil. 2023. Notes on Complexity: A Scientific Theory of Connection, Consciousness, and Being. First edition. New York: Spiegel & Grau.

Vopson, Melvin M. 2019. “The Mass-Energy-Information Equivalence Principle.” AIP Advances 9 (9): 095206. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5123794.