Regenerative Revolution: Flow, Transparency & Bio-Centricity

- Regenerative Revolution: Introduction

- Flow: Participatory Communication & Co-Creation

- Transparency: Limits & Blockchain

- Bio-Centricity: Ethical Technology & AIoT on the Edge

In succession to a post I published a few weeks ago, this post forms the continuation and is titled the "Regenerative Revolution", which will form a series of posts that will look ahead into the sustainability and regenerative transition. But we will not be doing this alone. I will lean into the works of many great thinkers and hopefully, through reasoning and informational osmosis, we will emerge with a coherent narrative that vaguely resembles a sensical and reasonable way forwards.

Let's begin.

Our First Guide - Prof. Raymond Williams

Raymond Williams, the 20th century intellectual and Professor at the University of Cambridge may seem like an unlikely character to illuminate the regenerative revolution that our planet so urgently needs; but much like Georges Lemaître and Nikola Tesla, his insights and thinking were truly ahead of his time. Since his thinking was so beyond his peers, he was also subjected to much criticism from the 'establishment'. His focus on real social equality, such as women's rights, empowering rural communities (as per his seminal book 'The Country and the City'), upholding indigenous traditions (his internationalism and solidarity with other subordinated cultures), protection of biospheres and focus on ethics; this drew criticism from his peers, as exemplified by the remarks of R. W. Johnson in 1990 (London);

"It seems, in the great tradition of British wooziness, to be all about values and community and wholeness; in a word, Christian socialism and brown bread." - R. W. Johnson

It's ironic really, 'values and community and wholeness' would go a long way towards addressing the multi-faceted challenges we face today. But what draws me to Williams is not his noble beliefs nor his inspirational vision for a near-utopian society, but rather, his remarkable instinct and pragmatic insight into how we could bring about such societal transformation, despite the incurred complexity.

In the last few weeks, I have read several noteworthy books, such as "Not the End of the World" by Hannah Ritchie and "Age of Resilience" by Jeremy Rifkin; discussing necessary future developments that will address the multitude of global challenges we are currently facing. These books offered some good insights ("Age of Resilience" is particularly excellent) and aimed to be solutions-focussed, but I felt that they somewhat lacked the realisation that scaled transformation is deeply contingent on a set of mutual beliefs and behaviours within a given society, as supported by recent studies.

Peculiarly, the most coherent rationale amongst such written narratives came from works written over half a century ago by the late Raymond Williams. A time before the term "Overshoot" was even yoked to the discourse of human progress. He was both a brilliant thinker and very curious character - he would not fit into any given cultural label if one was so inclined, apart from being regarded as 'Welsh' of course (which derives from the old Germanic word walha, meaning outsider). Ironically, it is rather befitting, since he certainly was an outlier amongst intellectuals and a paragon of critical thinking. He was the Noam Chomsky of his day, but I reserve caution in drawing this very loose comparison. Much like Chomsky, he was unique in his way of thinking and many of his writings were so inherently cross-cutting with respect to academic disciplines, they often struggled to know where to publish his work. But Raymond Williams also had an uncannily prophetic ability that is seldom observed in modern times;

Williams's knack for prophecy, like his abstractions, has been seriously undervalued...In my brief comments, I shall suggest that Williams's major contribution to our present-day challenges is not simply that he taught us how to think historically about cultural practices or how to approach political matters with a subtle cultural materialist orientation in a manner that stands head and shoulders above any of his generation. Rather, Williams speaks to us today primarily because he best exemplifies what it means for a contemporary intellectual leftist to carve out and sustain, with quiet strength and relentless reflection, a sense of prophetic vocation in a period of pervasive demoralization and marginalization of progressive thinkers and activists. His career can be seen as a dynamic series of critical self-inventories in which he attempts to come to terms with the traditions and communities that permit him to exercise his agency and lay bare the structural and personal constraints that limit the growth of those traditions and communities. - Cultural materialism: on Raymond Williams. (University of Minnesota Press, 1995).

His written works, befitting of a modern-day Bard, resonate today stronger than ever. In this brief post, I aim to illustrate that his book The Long Revolution, is in its essence, an attempt to capture the 'regenerative' movement that we know today.

Regenerative agriculture’s aim is to regenerate “the health, vitality, and evolutionary capability of whole living systems.” Regenerative Agriculture Part 1: The Philosophy. (2020).

As noted by Ethan Soloviev, this regenerative movement cannot be defined in a static assemblage of words, since it is by its very trajectory, a movement towards something more wholesome, which Williams tried to articulate;

His term is a claim: that there is a historical process that is hard to comprehend because we are all within it, and it is that which he is attempting to articulate for the first time...He argues that we are within a far-reaching transformation – one that brought forth the very terms such as ‘democracy’, ‘industry ’, ‘culture’, ‘art’ and ‘class’ that we use to describe and measure it. Its transformation will take – has already taken – centuries. It is necessarily lengthy and multi-generational: ‘Everything that I understand of the history of the Long Revolution leads me to the belief that we are still in its early stages’. - Anthony H. Barnett, MD, FRCP, Professor of Medicine in the University of Birmingham, Author of Introduction: Williams, R. The Long Revolution. (Parthian Books, 1961).

Williams was clearly a prolific 'systems thinker', and what truly stands out for me is his observance that our future on this planet is contingent on a radically improved 'communication system' that truthfully captures the inter-relations, informational flows and hegemonic forces within global societies (see Cultural materialism).

A simplified example: There is very little merit in addressing the fossil-free energy crisis with a globally decentralized strategy such as a solar super-farm in the Sahara supported by local mini-fusion reactors using safer inertial-fusion if; a) all do not agree on the premise of going fossil-free, or, b) disapprove of the displacement of the indigenous Saharawis or c) their stance on proximal mini-fusion reactors in the countryside. A handful of elites and electives may pass this motion, purely due to asymmetry of information when conducting the decision but the result would not be representative of a truly participatory democracy. This is termed as 'waste' within a communication system by Williams, something we will revert back to later on in this essay. Coincidently, this 'waste' can also be paralleled with 'presumed consent', as coined recently on Planet: Critical by George Monbiot.

In contrast to a decentralised participatory democracy, some voices will naturally be under-represented and power-dynamics may unfortunately factor in. It is becoming increasingly clear that we need a radically improved understanding on how to implement a decentralised 'participatory democracy' and a collective rethink on our attribution of 'value', if we are to address the pressing challenges of a changing climate, conflicts and inequality (as also detailed in an older post). Jane Fonda really drove this message home recently by illustrating how a sick planet essentially makes us sick and more prone to diseases such as cancer. But these challenges also go beyond anthropocentric bounds and we ought to revaluate our inflated anthropocentric perspective - we are currently poor stewards and our living 'planet is in peril'.

This 'Long Revolution' is an attempt to create a vision of a more equitable society, that attributes ultimate value to the health and vitality of whole living systems, which can be appreciated as a significant abstraction (but not complete departure) from the free-market capitalism of today. How far and what bounds this abstraction ought to embody, I am unclear. Others such as David Korten have envisioned this abstraction as the Ecological Civilization, which also parallels the recent Dasgupta Review - it highlights this ”blind spot” that nature has been siphoned into within the capitalism of today.

But as I will demonstrate later in this post, our "untethered" capitalist system is currently at complete odds with evolutionary systems and nature. Whether intentional or not, we ought to realise this causality.

He intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. —Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations

In this regard, I certainly acknowledge the phenomena of emergence within complex adaptive systems (i.e. our global economic system) and I reserve some hope that big-data and deep learning can help foster a better grasp of causality within this complex system (I will revert back to this theme later in the series). I would hearken the inspiration of others here, since global economics is not my field of expertise, despite some underlying interest in complex adaptive systems. After all, this regenerative movement is a complex co-creation project on a truly global scale. In this regard, we must humbly acknowledge our radial limits of knowledge and seek much well-meaning guidance.

As noted previously, what I find compelling about Williams is his general political abode, which certainly reflected the phenomena of emergence as he progressed through life. Much like how Marx’s own observation that he was not a Marxist (with its implied and historically-known perils), Williams's self-identification concluded on some form of hybridity between a participatory democracy, decentralised libertarianism (contrary to the limited conception of 'sovereign individual' economics, as coined by Williams) and a form of "Ecosocialism".

“Bringing these issues together, then, we can see that in local, national and international terms there are already kinds of thinking which can become the elements of an ecologically conscious socialism. We can begin to think of a new kind of social analysis in which ecology and economics will become, as they always should be, a single science. We can see the outline of political bearings which can be related to material realities in ways that give us practical hope for a shared future.” - Williams, R. & Blackburn, R. Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism. (Verso, London, 1989).

“The politics of the New Right, with its version of libertarianism in a dissolution or deregulation of all bonds and all national and cultural formations in the interests of what is represented as the ideal open market and the truly open society, look very familiar in retrospect. For the sovereign individual is offered as the dominant political and cultural form, even in a world more evidently controlled by concentrated economics and military power.” (Williams 1988a: 62) — Higgins, J. Raymond Williams: Literature, Marxism and Cultural Materialism. (Routledge, London, 2004).

Reflecting on the above, it does beckon the question, can a certain abstracted conception of the ‘sovereign individual’ help free-market capitalism evolve towards a more decentralised human-ordered and eco-complex concept, such as a ‘sovereign biome’? It seems to be the subverted pretext to much of Williams’ thoughts.

I recognise that these realms may be self-contradictory in some aspects, but as I will later demonstrate in the series, logic within complex adaptive systems (i.e. our reality) is unavoidably self-contradictory. Whether this forms a viable way forwards, I do not know - I remain a mere observer, receptive of 'emergence' and open-minded. However, I do believe we should be hesitant with 'labels', since they inherently assume a set of preconceptions, which may or may not be true. In my own limited experiences in discussing these matters in various spheres, I believe I would be in good company to merely be in the position of 'wanting a future whereby all living systems thrive within planetary boundaries'. Naturally, this position can inherit whatever label the future decides, but for now I seek to avoid the demarcation risks of "anti-", "de-" and "-ist" labels.

A Vision for a Participatory 'Global Village'

In light of the global-scope of our current challenges, I do believe, as per Williams's utopian vision for a 'global village', that planetary problems require planetary solutions. In this respect, technology can play a critical role (something I will revert to in later posts within this series). The need for greater transparency and understanding on the degree of interdependence and requirements of artifacts, which sustain our capitalist system, is difficult to overstate. The impacts of our "consumptive patterns" can have unforeseen effects, as tragically illustrated by the story of Easter Island.

For the people of Easter Island, for example, deepwater canoes had been part of daily life for thousands of years before their ancestors reached this westernmost outpost of Polynesia. This may be among the core reasons that nobody on Easter Island anticipated the consequences of cutting down too many trees. The resulting deforestation eliminated large tree trunks, an essential resource without which deepwater canoes could not be made, cutting off the majority of the island’ s food supply and, at the same time, the only way out of the trap the Easter Islanders set for themselves. The canoe had been so omnipresent a part of life for so long that the possibility of its absence very likely never entered into the islanders’ darkest dreams. - Greer, J. M. The Ecotechnic Future: Envisioning a Post-Peak World. (New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, BC, 2009).

Such consumptive patterns within our current "untethered" capitalist system, which do not directly meet real needs or contribute to both human well-being and planetary flourishing, must be subjected to some form of means-tested cogitation. This would likely play its role in the necessary abstraction or significant evolution of capitalism, whatever shape or form this may take.

I may be wrong in my inferences here, but I believe we need a balanced approach in enacting this transition (e.g. a recent radical incrementalism strategy), and as Hans Rosling elucidated in his book 'Factfulness', the free-markets have played a significant part in some progress within modern medicine, alleviating poverty and reducing child mortality rates in the developing world. But I believe there is significant room for improvement and it is urgently needed - global poverty, biodiversity loss and significant inequality (in all its guises) still remain at large.

A Globally Indigenous 'Communication System'

But how do we address such global issues? To echo a recent point, planetary problems require planetary solutions and in this respect, we urgently require a system of communication that befits global society. In this regard, Williams' insights are noteworthy.

Every society has communication systems, and these can be of a kind which at first we don’t think of as communication systems at all. One very good example is of some prominent feature in the place where we live. Think how much of our sense of where we live can be expressed in some prominent building, some hill, some feature, natural or man-made. This we feel somehow expresses the meaning of what it is to live in that place, and around that building, around that feature, we very often feel ourselves to belong. Some of the deepest emotions human beings can have are emotions about such a place, which in a way has been their community, their society. Yet the hill is saying nothing. The building of course was specially created: it was put there, often, to express the community’s sense of itself, some value it held in common. Because it lasts it goes on expressing that value, and when new people see it, they can get the same value back from it as its builders put in. Or sometimes they get a new value, and see it in different ways. But there the things are, built right into the structure of what it feels like to belong to a group, to belong to a community, to belong to a society. After these of course there are the more formal communication systems: the language of the group, and all the institutions religious institutions, institutions of information, sometimes of command, institutions of persuasion, institutions of entertainment, institutions of art – all communication systems which in much the same way – you can see this very clearly in simple societies – are right at the centre of what it feels to be a member of that society. The relations between people in the society are often seen most easily by looking at the institutions of communication – how the people regard each other, what things they think important, what things they choose to stress, what things they choose to omit. - Williams, R. & Blackburn, R. Resources of hope: culture, democracy, socialism. (Verso, 1989).

This mirrors sentiments from indigenous languages, such as the Welsh "cynefin" and the Te Reo Māori "tūrangawaewae", anchoring identity in communal belonging within a local biosphere. Furthermore, to further illustrate this crucial point, we could supplant this notion of a hill in the example above with the Rakaia river in New Zealand, which so eloquently captures this systemic interplay of culture, communication and value attribution:

There is a river in New Zealand called the Rakaia that is spanned by a suspension bridge of novel design. There is a notice by the bridge that tells its history and that of the ford that existed before the bridge. The river is wide and fierce, draining water from the Southern Alps. The notice says that before the bridge was built, the Maori would cross the river in groups, each group holding a long pole placed horizontally on the surface of the water so that the weakest would not be swept off their feet. The people who came after the Maori, who knew how to build a bridge of iron supported from beneath, but who did not understand why a group of people would cross a river with a pole, wrote the notice. Crossing together was, in fact, not to protect the weakest, but to protect the entire group. Any individual trying to ford a fast-flowing river draining glacial waters runs a great risk. If you hold onto a long horizontal pole with others, you are at much lower risk. The concept of ‘from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs’ was a concept that took shape in places and times when it was better understood that all benefited as a result. When crossing a freezing river with a pole, you need as many others holding onto that pole with you as can fit. - Dorling, D. Injustice: why social inequality still persists. (Policy Press, 2015).

Let me briefly pause now to explain how Raymond Williams can help revive this aforementioned notion of ‘from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs’ and guide us towards developing a more regenerative future. By recognizing the early stages of societal transformation and the necessity for a change in fundamental forms of relationships, Williams' work can guide us towards developing a more regenerative future that is truly community-centric, eco-centric, and techno-centric.

The significance of our interconnectedness amongst ourselves and nature is a beckoning call for a rethink in our attitudes towards nature and the development of healthy and vibrant societies that work alongside nature. This involves making new connections in the human and social order, forcing into consciousness the suppressed connections, and seeing Earth's living systems and social order as a "fuzzy" and interconnected whole. The contrasting matter of Trophic Cascade and the recent culling attempt of Wolves in Switzerland, attests to our void of understanding here. Admittedly, this is a complex task and our journey in acknowledging this interconnectedness of our reality is in its infancy. In many ways, Hawking's outlook about the future resonates strongly with this sentiment;

'I think the next [21st] century will be the century of complexity' - Stephen Hawking

Mega-synthesis in the tangential, and therefore and thereby a leap forward of the radial energies along the principal axis of evolution : ever more complexity and thus ever more consciousness. If that is what really happens, what more do we need to convince ourselves of the vital error hidden in the depths of any doctrine of isolation? The egocentric ideal of a future reserved for those who have managed to attain egoistically the extremity of 'everyone for himself' is false and against nature. No element could move and grow except with and by all the others with itself. - De Chardin, P. T. The Phenomonen of Man. (Harper Perennial, New York, NY, 2008).

As Williams and others have stressed, the Utopian future will be more rather than less complex than now, as subjectivity is given new opportunities outside the constraints of a dominant capitalism. Thus we have to have recourse to past models as the only way of figuring this future, without losing sight of their inevitable limitations. In the field of electronic communication, for instance, he envisages an appropriation, such that 'the kinds of democracy previously imagined only for very small communities [. . .] become quite normally available for larger communities'. - Raymond Williams Now: Knowledge, Limits and the Future. (Macmillan Press, Basingstoke, 1997).

As noted previously in my article, juxtaposing Williams' foretelling of future developments with the advent of Blockchain and Edge Computing rings unnervingly true. He really did have an uncanny knack for prescribing future trends.

Williams’ Non-Subordination Leadership

I suppose like many in the world, the looming future of a changing climate, global conflicts, inequality and ecological challenges can be a compelling prompt for reflection. In many respects, the state of change in our world is as foundational as entropic gravity, as the Greek philosopher Heraclitus noted in the 6th century;

“The only constant in life is change.”- Heraclitus

But when the waves of change occur too rapidly and coherently, it can seem overwhelming. Given such a muti-faceted backdrop of change, the convening of the global elite and prominent thinkers at the World Economic Forum in Davos this week stood in particular contrast to this cacophony of issues. Much like the precedence to this event, there will be significant dialogue around the collective commitment in addressing climate change and the pivotal role of AI-enabled technological advancements as part of this mitigation narrative. Such cross-cultural participatory dialogue is very much needed and I believe forums of such kind can yield very positive outcomes. However, one must also recognise our own guised biases, which couples our thinking towards narratives that can often be congruent with self-interests, whether economical, political or geographical. In response to this, we may mitigate this by leaning into ideological systems that are seemingly more altruistic and socialistic, founded upon a greater appreciation for the other and collective ownership. In its theoretical essence, this is both wholesome and is seemingly fairer for all. However, as Argentinean President Javier Milei rightly cautioned during the event, our material understanding of culture is also inherently understood through the aperture of our shared history; both in triumphs and tribulations.

Today I’m here to tell you that the Western world is in danger. And it is in danger because those who are supposed to have to defend the values of the West are co-opted by a vision of the world that inexorably leads to socialism and thereby to poverty. Unfortunately, in recent decades, the main leaders of the Western world have abandoned the model of freedom for different versions of what we call collectivism. Some have been motivated by well-meaning individuals who are willing to help others, and others have been motivated by the wish to belong to a privileged caste. We’re here to tell you that collectivist experiments are never the solution to the problems that afflict the citizens of the world. Rather, they are the root cause. Do believe me: no one is in better place than us, Argentines, to testify to these two points. - Source

Williams' emphasis on the creative capacity of working people, the importance of achieving an acceptable human order, and the critique of socialism for focusing on political and economic orders rather than a human order indicate a focus on facilitating a participatory democracy that respects individual rights and agency rather than the inherent dangers (and historical forms of socialism) of a collectivist approach.

If man is essentially a learning, creating and communicating being, the only social organization adequate to his nature is a participatory democracy, in which all of us, as unique individuals, learn, communicate and control. Any lesser, restrictive system is simply a waste of our true resources. - Williams, R. The Long Revolution. (Parthian Books, 1961).

From his egalitarian perspective Williams was suspicious of leadership. Even to talk in those terms could contribute to a politically and culturally subordinated people. - Eldridge, J. & Eldridge, L. Raymond Williams: Making Connections. vol. 46 (Taylor & Francis, 2005).

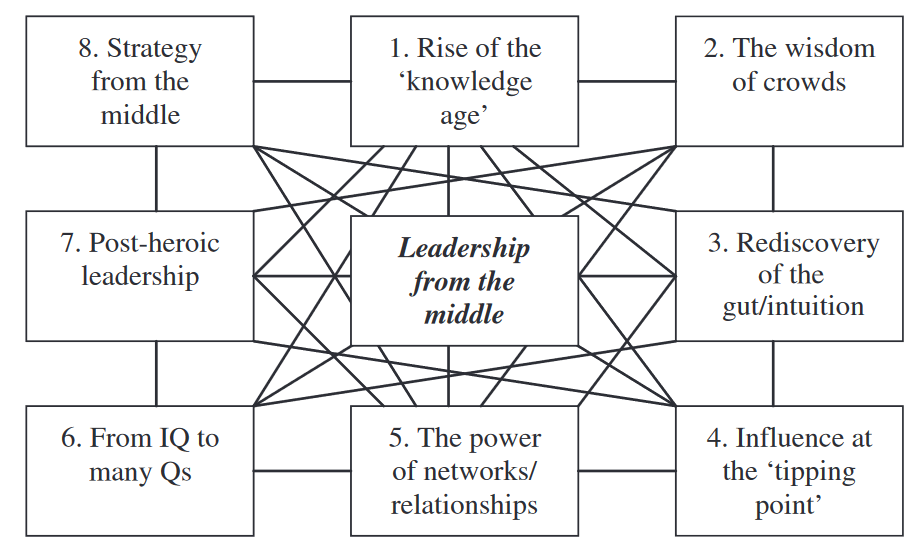

In times such as today, if we have learnt anything from the giants of technology (such as Google) and servant/transformational leadership frameworks (please refer to this older post); the most impactful frameworks lean more into 'orchestration' and 'leading from the middle', which are evidentially far more effective forms of leadership for empowering innovative ideas when faced with complexity.

Leading from the middle allows the leader to toggle between ‘envisioning’ (mapping and sussing a vision) and ‘interacting’ (linking and promoting with ideas and perspectives inside and outside the organization). This connection between envisioning and interacting is articulated by two other modern leaders. Terry Leahy, CEO of supermarket giant Tesco, claims that leadership to him ‘means enabling people to achieve more than they could on their own. In a practical sense, this means having vision, leading by example, motivating and inspiring.’ Michael Stedman, CEO of Natural History New Zealand, one of the world’s largest makers of documentary programming, puts it this way: ‘The way I like to think of my job [as a leader] is that it’s like being a squash ball. I’m doing my job when I’m bouncing around the different parts of this company, connecting ideas and sparking things off.’ - Bilton, C. & Cummings, S. Creative Strategy: Reconnecting Business and Innovation. (Wiley, Chichester, West Sussex [England], 2010).

Oftentimes, we can be unaware of this biased-coupling for 'power' or 'control', which manifests itself in our cultural practices through complex and convoluted ways. But Williams believed that this was the most ethically sound and harmonious way forwards.

Barnett comments: ‘He wanted people to be at home with themselves and each other. He knew that this could demand an extremely tough and complex struggle for power, yet people had to undertake it for themselves’ - Eldridge, J. & Eldridge, L. Raymond Williams: Making Connections. vol. 46 (Taylor & Francis, 2005).

But before we delve deeper into this series, let us briefly recap on the governing premise underlying the need to address such global challenges; it is addressing a concern for meeting both human and nature's needs within the Earth's terrestrial bounds. Naturally, the stakeholders in addressing such a challenge is the entire biome of planet earth and any progressive dialogue should be participatory in its entirety. Sadly, a cuttlefish can't talk (yet), but if it did, it would likely not subscribe to a anthropocentric worldview. Our oceans are suffering (e.g. unprecedented sea surface temperatures) because of our current patterns of living.

What would the World Economic Forum look like in a truly participatory democracy? Naturally, we are not yet privileged with a low-power solar-driven wearable that enables the entire population of earth to participate in such crucial WEF-like dialogues, there will always be some element of information asymmetry and 'waste' within current communication systems. Given such inherent limitations, the ethical concern for 'our fellow neighbour', whether a foreign nation, indigenous peoples, future generations or delicate biosphere, should act like the foundational fibre that mediates such dialogue;

If the ways in which we choose to talk to one another are becoming crucial to modern society, then we must find ways of doing so that are ethically rather than technologically and economically guided. - Raymond Williams now: knowledge, limits and the future. (Macmillan Press, 1997).

Author's update: since writing this article I have been made aware of the Raymond Williams Society, https://raymondwilliams.co.uk/, which has many great resources that go further into his thoughts and ideas.

Please stay tuned for this series of "Regenerative Revolution" posts, up next:

- Flow: Participatory Communication & Co-Creation

Thanks for taking the time to read this post and until next time,

Best wishes,

Aaron